The hum of the refrigerator is a modern constant, a sound so familiar we barely notice it. Yet, for the vast majority of human history, this technology did not exist. Our ancestors faced the same fundamental challenge we do: securing a safe, stable food supply. Their solutions, born of necessity and ingenuity, were remarkably effective and laid the groundwork for the culinary world we know today. How did they manage to keep meat from spoiling, preserve the summer harvest for a barren winter, and ensure their families were fed through times of scarcity? The methods for storing food before refrigerators were diverse, leveraging natural elements like salt, smoke, ice, and fermentation to create a resilient pantry. In this guide, we will explore these timeless techniques, many of which are experiencing a renaissance among modern homesteaders and preparedness enthusiasts. In an age of supply chain fragility, understanding these lost arts is not just a historical curiosity—it’s a key to greater self-sufficiency and food security for your family today.

Table of Contents

Understanding Food Spoilage and the Race Against Time

Before diving into the specific methods, it’s crucial to understand the enemies our ancestors were fighting: microorganisms. Bacteria, yeasts, and molds are everywhere, and they find our food just as delicious as we do. For these tiny organisms to thrive, they need a few key things: moisture, a comfortable temperature (typically between 40°F and 140°F, the “danger zone”), and time. The entire goal of traditional food preservation was to create an environment where these microbes could not survive or multiply.

This battle was a race against time. A fresh kill from a hunt or a basket of ripe vegetables would begin to break down within hours if left untreated. The techniques developed were essentially ways to manipulate the food’s environment. They worked by:

- Removing Moisture: Microbes need water to live. Methods like drying, salting, and smoking work by drawing water out of the food and the microbial cells themselves, effectively dehydrating them to death.

- Altering Acidity: Most harmful bacteria cannot survive in a highly acidic environment. Fermentation, and later pickling with vinegar, created this inhospitable acidic condition, allowing beneficial bacteria to thrive while killing off dangerous pathogens.

- Lowering Temperature: While mechanical refrigeration is new, the use of cold is not. Underground root cellars, ice houses, and spring houses leveraged the earth’s consistently cool temperature to significantly slow down microbial growth.

- Creating a Biological Barrier: Techniques like confit (preserving in fat) or burying certain foods in grains created a physical barrier that prevented oxygen and new contaminants from reaching the food.

These principles were understood intuitively and through generations of trial and error. The successful application of these methods meant the difference between a well-fed community and starvation during a long winter. This foundational knowledge is the basis for [creating a modern survival pantry](INTERNAL LINK PLACEHOLDER), blending old wisdom with new resources.

The Pantry of the Earth: Root Cellars and Cool Storage

One of the most widespread and effective methods of preserving food without refrigeration was the root cellar. This was not a single design but a concept: utilizing the earth’s natural insulation and stable, cool temperature to store a variety of foods for months. The ground below the frost line maintains a relatively constant temperature, typically between 50°F and 60°F depending on the region, which is ideal for slowing respiration and decay in vegetables and fruits.

A root cellar could be as simple as a hole in the ground lined with straw and covered with a wooden door, or as elaborate as a stone-lined chamber built into a hillside. The key was consistent humidity and ventilation. Crops like potatoes, carrots, beets, turnips, and cabbages were harvested in the fall and carefully placed in the cellar. They were often packed in sand, sawdust, or leaves to maintain humidity and prevent them from touching, which could spread rot. Apples could be stored on shelves, imparting a pleasant aroma to the space and, curiously, helping to prevent potatoes from sprouting.

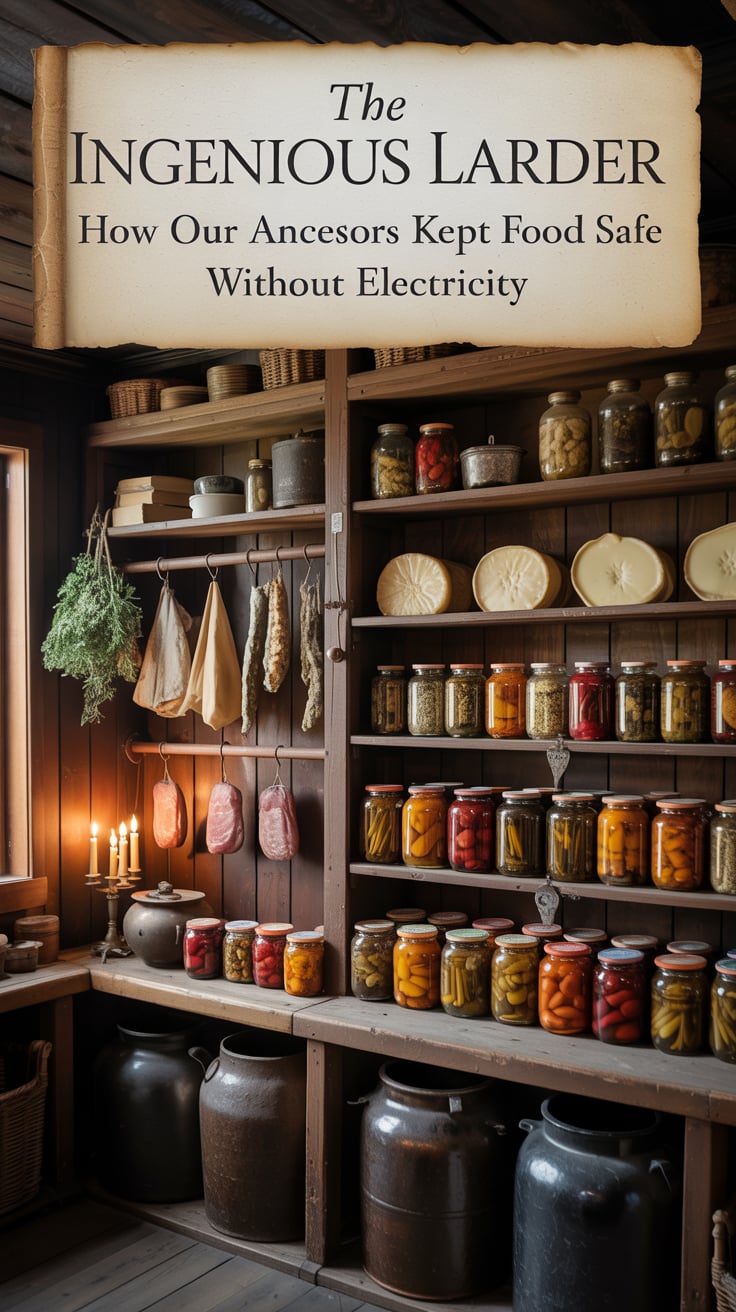

Beyond the dedicated root cellar, many homes had other cool storage areas. A “spring house” was a small building constructed over a flowing spring, using the constantly cool water to chill containers of milk, butter, and cream. In many parts of Europe, homes were built with “larders”—small, north-facing rooms with stone floors and slatted windows designed to maximize air circulation and keep contents cool.

The principles of cool storage are perfectly applicable today. Even without a cellar, you can store root vegetables in a cool, dark basement, garage, or closet. Modern alternatives like the Aqua Tower leverage this ancient principle on a smaller, more efficient scale, providing a gravity-fed water filtration and storage system that keeps water cool and safe, much like a spring house would have. Understanding how to manage temperature and humidity without electricity is a cornerstone of food independence.

Salt and Smoke: The Dynamic Duo of Preservation

If root cellars were for plants, then salt and smoke were primarily for protein. These two methods, often used in tandem, are some of the oldest and most effective ways to preserve meat and fish. Salt works through a process called osmosis; it draws the moisture out of the cells of both the meat and any bacteria present, making the environment too dry for microbial life. Smoke adds a second layer of protection.

There are two primary salting methods:

- Dry Curing: Meat or fish is thoroughly packed in coarse salt, sometimes mixed with sugar and spices. The salt pulls out moisture, creating a brine that is then drained away. This results in a very hard, salty product like salt cod or country ham.

- Brine Curing (Corning): The food is submerged in a heavily salted water solution, often with spices. The brine penetrates the meat, preserving it and flavoring it throughout. Corned beef is a classic example.

After salting, smoking was often the next step. Smoking further dehydrates the meat and deposits phenolic compounds from the smoke onto its surface, which have antimicrobial and antioxidant properties. There are two types of smoking:

- Hot Smoking: This cooks and flavors the meat simultaneously, but it doesn’t preserve it for as long. It’s done at higher temperatures.

- Cold Smoking: This is the true preservation method. The meat is smoked at low temperatures (below 85°F) for extended periods, sometimes days. This fully preserves the meat without cooking it, resulting in products like smoked salmon or traditional jerky.

These methods created stable food sources that could be stored for months or even years. Pemmican, a North American Indigenous invention, took this further by combining dried, pounded meat with rendered fat and sometimes berries, creating a compact, incredibly nutritious, and long-lasting survival food. Modern resources like The Lost SuperFoods delve deep into these powerful preservation techniques, documenting over 126 forgotten survival foods and showing how you can make them today to secure your own food supply. Furthermore, for a reliable source of clean water to complement your food stores—a critical element in any preservation scenario—the Joseph’s Well system offers an advanced solution for creating a safe, long-term water reserve.

The Power of Fermentation and Pickling

Fermentation is a biological miracle, a form of preservation that not only saves food but often enhances its nutritional value and digestibility. Unlike other methods that seek to destroy all microbial life, fermentation encourages the growth of beneficial bacteria (like lactobacillus) that create lactic acid. This acid acts as a natural preservative, preventing the growth of spoilage-causing bacteria.

This process was used globally to preserve a vast array of foods:

- Vegetables: Sauerkraut (fermented cabbage) and kimchi are the most famous examples. Almost any vegetable can be fermented, from cucumbers to carrots to beets.

- Dairy: Before refrigeration, milk would spoil quickly. Fermenting it into yogurt, kefir, or cheese was a way to extend its shelf life dramatically. Hard cheeses, in particular, could be aged for months.

- Beverages: Fermentation also produced stable beverages. Beer and wine were often safer to drink than contaminated water sources, and they provided valuable calories.

Pickling is a related but distinct process. While fermentation uses bacteria to create acid, pickling involves submerging food in an acid (usually vinegar) to achieve the same preserving effect. This is a faster process and was used for everything from onions and eggs to walnuts.

The beauty of fermentation and pickling is its accessibility. It requires no special equipment and very little energy. A jar, some salt or vinegar, and vegetables are all you need to get started. This “living” food provided our ancestors with a vital source of probiotics, supporting gut health and immunity long before these concepts were scientifically understood. For those interested in expanding their self-reliance skills beyond food, understanding [essential home medical supplies](INTERNAL LINK PLACEHOLDER) is a logical next step, with resources like Home Doctor providing a practical guide for when professional medical help is not available.

Drying and Dehydrating: The Ultimate Simplification

Drying is arguably the simplest and most ancient form of food preservation. By removing the water content, you remove the element that all life requires. Sun, wind, and fire were the original tools for this task. Nearly every culture has a tradition of dried foods, from the jerked meats of the Americas to the dried fish of Scandinavia and the dried fruits of the Mediterranean.

The methods varied by climate:

- Sun Drying: In hot, dry climates, foods like grapes (to make raisins), figs, tomatoes, and peppers were simply laid out in the sun for several days. This method required low humidity to prevent mold.

- Air Drying: In cooler or more humid climates, food was often hung in the rafters of homes near the hearth, where the ambient heat and smoke could slowly dehydrate it. Herbs, garlands of onions, and strings of chilies were common sights.

- Oven Drying: As enclosed ovens became more common, their residual heat after baking could be used to dry slices of fruit or meat.

Dried foods are incredibly space-efficient and lightweight, making them ideal for travel and long-term storage. A bushel of apples reduces to a fraction of its volume when dried into rings. A side of beef becomes a few pounds of durable, protein-rich jerky. The key to successful drying is doing it quickly enough to prevent spoilage during the process and then storing the finished product in absolutely airtight conditions to prevent it from reabsorbing moisture from the air.

This principle of creating compact, long-lasting nutrition is at the heart of modern preparedness. While our ancestors dried meat over a fire, today’s survival strategies encompass digital security and urban readiness. Programs like URBAN Survival Code teach critical skills for navigating crises in a modern landscape, while BlackOps Elite Strategies focuses on advanced financial and personal security protocols. For securing the most vital resource—water—the SmartWaterBox provides a modern solution for purification and storage, a critical companion to any stockpile of dried foods.

Ice and Insulation: The Precursors to Mechanical Cooling

The idea of using ice to preserve food is not new. For centuries, people in cold climates harvested ice from lakes and rivers during the winter and stored it in “ice houses” to use throughout the year. These structures were marvels of passive engineering, often built partially or completely underground and insulated with materials like straw, sawdust, or wood shavings. A well-built ice house could preserve ice well into the summer months.

Wealthy estates and, later, cities, had large commercial ice houses. The ice would be cut into blocks, transported, and sold to households who would place it in an “icebox.” The icebox was a insulated cabinet, typically made of wood and lined with tin or zinc. A block of ice placed in a compartment at the top would cool the air inside, and as the air cooled, it would sink, creating circulation. A drip pan underneath would collect the meltwater, which needed to be emptied daily.

This system was the direct predecessor to the electric refrigerator. It required a robust supply chain for harvesting, storing, and delivering ice. The famous “Ice King,” Frederic Tudor, made a fortune shipping New England ice to places as far away as the Caribbean and India. The limitations were obvious: dependence on cold winters, the labor involved, and the constant need to replenish the melting ice. However, for its time, it was a revolutionary way to keep perishables like fresh milk, meat, and leftovers cool for short periods. This historical approach underscores the importance of a sustainable water supply, a need that modern systems like the Aqua Tower are designed to meet with efficiency and reliability.

Lessons for the Modern Homestead and Preparedness Plan

The knowledge of how our ancestors stored food before refrigerators is more than a history lesson; it is a toolkit for resilience. In a world of just-in-time delivery and complex supply chains, a power outage or major disruption can render a modern kitchen’s contents unsafe in hours. By relearning these techniques, we can build a buffer against uncertainty.

Integrating these methods doesn’t mean abandoning modern convenience. It means supplementing it with wisdom that provides security and satisfaction. Start small:

- Ferment: Make a jar of sauerkraut. It’s simple, cost-effective, and incredibly good for you.

- Dehydrate: Use your oven on its lowest setting to dry apple slices or make beef jerky.

- Learn to Can: While canning is a more modern invention (early 19th century), it is a logical extension of these principles, using heat to sterilize and seal food in glass jars.

- Build a Modern “Root Cellar”: Even apartment dwellers can use coolers and balconies to store root vegetables, or invest in a high-quality cooler that can keep items cold for days.

The mindset is as important as the methods. Our ancestors thought seasonally and locally. They understood the rhythms of harvest and the necessity of preparation. Modern resources are designed to help you adopt this mindset efficiently. For instance, Dark Reset is a new survival offer that provides insights into digital privacy and security—the modern equivalent of safeguarding your winter stores.

By combining the timeless principles of food preservation with modern tools and knowledge, you can create a robust plan for your family’s well-being. This isn’t about fearing the future; it’s about confidently reclaiming the skills that ensure we thrive, no matter what it holds. The ultimate goal is a comprehensive strategy, and offers like the New Survival Offer can provide a curated starting point for building a resilient lifestyle.

Conclusion: Embracing the Past to Secure the Future

The story of stored food before refrigerators is a profound testament to human ingenuity. Our ancestors were not primitive; they were masters of their environment, using observation and intelligence to develop a sophisticated arsenal of preservation techniques. From the constant cool of the root cellar to the transformative power of fermentation, these methods provided food security, nutritional diversity, and cultural identity. They understood that preservation was not just about survival, but about thriving through the seasons.

Today, this knowledge offers us freedom. It frees us from total dependence on a fragile electrical grid and complex global systems. It connects us to our food in a deeper, more meaningful way. Whether you are a gardener with a surplus, a homesteader seeking greater independence, or a family simply wanting to be prepared for unexpected events, these time-tested strategies are invaluable. Start by learning one skill, preserving one food, and building one week’s worth of supplies. The journey toward self-reliance is a step-by-step process, deeply rooted in the proven practices of the past and supported by the intelligent resources of the present. By looking back, we can move forward with greater confidence, security, and resilience.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What was the most common way to preserve food before refrigeration?

There wasn’t one single “most common” way, as methods were highly regional and depended on the food type. However, drying (for meat, fish, and fruit) and cool storage in root cellars (for vegetables) were among the most widespread and fundamental techniques used across the globe.

How did pioneers keep meat from spoiling?

Pioneers relied heavily on salting (either dry-curing or in brine) and smoking to preserve meat. These methods removed moisture and created an environment where bacteria could not grow, allowing meat to be stored for many months.

What foods were stored in a root cellar?

Root vegetables like potatoes, carrots, turnips, and beets were cellar staples. Other common items included cabbages, onions, apples, pears, and canned or preserved goods. The cool, humid, and dark conditions were perfect for these crops.

Can you still use these old-fashioned preservation methods today?

Absolutely. In fact, there is a major revival of these skills today. Fermentation, dehydrating, and even basic root cellaring are popular among those interested in healthy eating, self-sufficiency, and homesteading.

How long would salted meat last?

Properly cured and stored salted meat could last for a year or more. It was often stored in barrels of brine or hung in a cool, dry place. Before cooking, it usually required soaking to remove excess salt.

What is the difference between pickling and fermenting?

The key difference is the source of the acid. Fermentation uses beneficial bacteria to naturally produce lactic acid. Pickling involves immersing food in an existing acid, like vinegar. Fermented foods are “live” with probiotics, while pickled foods are not.

What did people use before ice boxes?

Before the widespread use of ice boxes in the 19th century, people relied entirely on the other methods discussed in this article: root cellars, salting, smoking, drying, and fermenting. Perishable items were often consumed very quickly after production or purchase.

Why is learning about old food preservation methods important now?

In our modern world, these skills provide a layer of security and independence. They can reduce food waste, improve health through probiotics, and ensure your family has food during power outages or other emergencies.